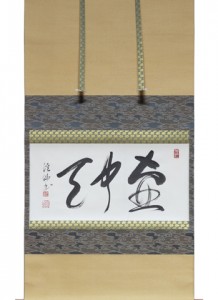

People beginning the practice of Zen Buddhism hope to attain awakening悟

Japanese: satori

, which they imagine is some extraordinary state of mind entirely free from deluded thinking. Later, when their practice matures, they may realize that there is no such thing: there is no special “reality” that is ever hidden away from us, there is only the ordinary working of our own bodies and minds (desires and fantasies included), directly experienced from moment to moment. The saying, “Always歴々

Chinese: li li

Japanese: rekireki

clear明

Chinese: ming

Japanese: mei

, openly堂々

Chinese: tang tang

Japanese: dōdō

exposed露

Chinese: lu

Japanese: ro

,” is an expression of that realization.

In the present painting of Bodhidharma by master Takahashi, the inscribed saying can be read either as a eulogy to the Indian monk, or as a quotation attributed to him. These exact words are not attributed to Bodhidharma in the classical literature of Zen, but they are reminiscent of a famous saying that is. Zen lore has it that when Bodhidharma first arrived in China and had a meeting with Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty (502-557), the latter asked him, “What is the ultimate meaning of the noble truths聖諦第一義

?” Bodhidharma replied, “Wide open and just so; there is nothing noble廓然無聖

.”

In locus classicus of the saying in Zen literature appears to be the Discourse Record of Zen Master Yuanwu Foguo圓悟佛果禪師語錄

, compiled by the disciples of Yuanwu Keqin圓悟克勤

(1063-1135):

A monk asked, “On account of what are the emperor and empress unable to grasp what is given [in the saying] ‘Always Clear, Openly Exposed’?” The master [Yuanwu] said, “In the hand of the Vajra there is an octagonal iron bar.”

僧問。明歷歷露堂堂。因什麼乾坤收不得。師云。金剛手裏八稜棒。

The expression translated here as “emperor and empress”乾坤

can also mean “heaven and earth.” The monk’s question, therefore, may refer to Emperor Wu of the Liang, who could not comprehend Bodhidharma’s utterance, “Wide open and just so; there is nothing noble,” or it may refer in a more general way to all the ordinary deluded beings of this world. What the monk asks, in effect, is why people become deluded about the nature of ultimate reality when, in fact, it is not hidden but entirely open to view. Yuanwu’s answer is open to interpretation. The “Vajra”金剛

he refers to are probably the pair of fierce “vajra strongmen”金剛力士

— deities who hold vajras (stylized thunderbolts) as weapons — who are represented in statues standing guard on either side of a Zen monastery gate. In general, vajra wielders金剛手

use their diamond-hard cudgels to smash evil spirits and destroy ignorance. Yuanwu thus implies that, just as malevolent spirits are prevented by the vajra wielders from entering a monastery, deluded people who are caught up in conceptual thinking about reality are thereby barred from seeing what is right in front of their faces.

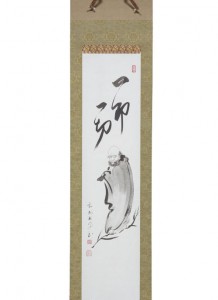

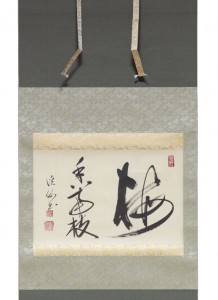

Bodhidharma (Darumazu 達磨図)

Bodhidharma菩提達摩 or 菩提達磨

Chinese: Putidamo

Japanese: Bodaidaruma

was an Indian Buddhist monk, a meditation master who was active in China in the early sixth century and came to be revered as the founding patriarch初祖

of the Zen lineage禪宗

in that country. Very little is known about the historical Bodhidharma, but his legendary biography grew in detail from the eighth through the eleventh centuries, and he became an emblematic figure much invoked thereafter in Zen literature and art.

According to traditional accounts, the Zen lineage was founded when the Buddha Śākyamuni conveyed his awakening — his “subtle mind of nirvāṇa”涅槃妙心

, which is “signless”無相

— directly to one of his disciples, the monk Mahākāśyapa, in what is characterized as a “separate transmission”別傳

that took place “apart from the teachings”教外

of the sutras. Mahākāśyapa later transmitted the “buddha-mind”佛心

to another monk, Ānanda, who became the second patriarch of the Zen lineage in India. The “mind-dharma”心法

, as it was also called, was subsequently handed down from master to disciple through the generations until it reached Bodhidharma, the 28th patriarch, who was charged by his master Prajñātāra (the 27th) with transmitting it to China.

The lore about Bodhidharma’s career in China includes many famous incidents. He is said to have “come from the west” by sea, arriving in 527 C.E. He immediately had an audience with Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty (502-557), whose avid patronage of Buddhist institutions he characterized as “having no merit”無功徳

. He then took up residence in the Shaolin Monastery少林寺

near Louyang, capital of the Northern Wei dynasty (386-535), where he spent nine years in meditation “facing a wall”面壁

. The monk Huike came to that monastery and was so ardent to be accepted as Bodhidharma’s disciple that he cut off his own arm斷臂

as an offering and was immediately instructed concerning true “peace of mind”安心

. Before returning to India, Bodhidharma recognized Huike as the second patriarch of the Zen lineage in China, stating that while other disciples had attained his “skin”皮

, “flesh”肉

,” and “bones”骨

, only the latter had “attained his marrow”得髓

. Bodhidharma, it is said, “only transmitted the mind dharma”唯傳心法

, no other teaching. With regard to his own method of instruction, he is often quoted as saying: “I point directly at the human mind吾直指人心

[so people may] see its nature and attain buddhahood見性成佛

,” and, “My method is to transmit mind by means of mind以心傳心

, without relying on scriptures不立文字

.”

Formal portraits of Bodhidharma (and all later patriarchs in his lineage) were first produced in Chinese Zen monasteries for use in annual and monthly memorial rites, when offerings of food and drink were made to those ancestral spirits. Later, all across East Asia, Bodhidharma also became an extremely popular subject of ink paintings inscribed with Zen sayings and used for decorative and didactic purposes. In keeping with his identity as an Indian monk, a “barbarian” from the west, he is conventionally depicted as a swarthy figure with a beard, earring, big nose, bulging eyes, and hairy chest. Moreover, in this ink painting by Zen master Takahashi, Bodhidharma’s body is outlined in a way that suggests the shape of the Chinese character for “mind” (心).